‘Clipper Maid of the Seas'

2011

kilt dimensions 747cms x 103cms Pole height 180cms

Michael Lisle-Taylor

Flag weave polyester, canvas, wood toggle, flagpole

I sat bolt upright on a blue canvas, flip down cargo seat, with no view, no intercom, no leg room and a flight time that was approaching geological. I entertained myself by touching the fuselage with the back of my flight deck helmet. Each contact with the bare airframe stringer, transmitted rotorhead vibrations through my helmet, skull and chattered my teeth. My set list alternated between dental renditions of Joy Division’s ‘Atmosphere' and The Clash’s ‘Clampdown’. To say there was no view, is slightly unfair, some meagre daylight did penetrate a small rectangle of perspex over my right shoulder. The view through it was mostly obscured by golden flows of sticky hydraulic fluid, leaking from the engine compartment above. But if you strained your eyes it was possible to catch a glimpse of the undercarriage support immediately outside. There was a second delightful vista, accessible through a hole in the aircraft floor. Although obscured partly by a transducer face, you could survey the passing landscape below, by undoing a few pop studs on the sonar well curtain. Above and around this signifiant porthole was a huge cable drum and winch assembly fitted with explosive cable cutting cartridges, display units and a radar. This monolithic unit took up most of the aircraft interior and cradled a dunking sonar, used to hunt Soviet submarines. The sonar well troop seat was the least desirable position on the aircraft, usually reserved for squadron pond life. I was the youngest and lowest rank on this stick and subsequently enjoying my seventh hour -with the fuel stop- cozied up against this Cold War crucial. Our Sea king was one of two aircraft, flying from the Naval Air Station at Culdrose in Cornwall to a sister station tenanted in a corner of Prestwick International Airport, on the Ayrshire coast in Scotland. This hallowed piece of ground was designated by the Royal Navy as the ‘Stone Frigate’ HMS Gannet. When we were there, Concorde pilots regularly practised take-offs and landing, but the airport also had a long history of fraternisation with the armed forces. The US military frequently used it as transatlantic hub for its personnel and equipment, from WW2 right through the War on Terror to the present day. It shipped all sorts from Sergeant Elvis Presley to the CIA’s extraordinary renditions heading for Guantánamo Bay. Our squadron had been tasked to provide protection to ‘Polaris’ nuclear submarines moving in and out of their base at Faslane. The squadron usually tasked with this job were having problems with modifications to their new aircraft, so we were stepping in. Head in my hands and elbows on my knees, I peered down at the passing border countryside, as we followed the roads North. I suddenly jolted back in disbelief to look around the cabin. Below us, a meteoric gash had torn up the landscape, cutting across fields from a dual carriage way right through a housing estate. Burnt out houses and a trail of debris scored a catastrophic line through the otherwise unremarkable Scottish scenery. I could see others in the air party with access to views and intercom, straining to see what I had just seen. As my mind asked if the Jocks had started a war, I lipread the resolving words from an aircrewman mouthing ‘Lockerbie’.

The Navy’s Sea King helicopters were real workhorses, thrown about the sky with liberal regard, in all sorts of conditions. They were constantly flipped from one role to another, from sub-zero Arctic operations in Norway to the dry abrasive sandy deserts of the Gulf states. But in the late 1980s their primary habitat was the salty grey expanses of the North Atlantic. They flew back to back four hour anti-submarine sorties. Like pollinating bees they hovered from one position to another dunking their sonic ears in the drink, to monitor our end of the strategic gap between Greenland, Iceland and the UK. Airtime was bracketed by punishing landings and launches from thrusting and plunging flight decks. My first front line draft was punctuated with its fair share of eventful landings. My poor old mum, picked up a ringing telephone on a number of occasions to hear “Mrs Lisle-Taylor? this is the staff officer 826 Naval Air Squadron, I’m afraid there’s been a crash, Michael is OK… but we wanted to let you know before you hear it in news….” The first time was one night, during work up exercises before deployment to the Persian Gulf. We were sailing in the Southern Approaches, ten miles from Eddystone lighthouse on RFA Resource when we launched our aircraft to collect Flag Officer Sea Training Staff from another ship. The helicopter lifted from the flight deck and a disorientated pilot took a lower than ideal flight path, into the dark swell, permanently dismantling one aircraft and two aircrewmen. We had only just exercised ‘aircraft ditch’ the day before and were trawling the floating debris in a crash boat within minutes, recovering the two survivors (link to book chapter).

Not long after this my dear old Mum had another chat with the squadron’s staff officer. Our flight had been embarked on RFA Fort Austin for an intensive but memorable exercise in the North Atlantic. One of the highlights being a collision with the aircraft carrier HMS Invincible fresh out of refit. The Fort Austin was an armament store ship and we were transferring munitions across to fill Invincible’s empty magazines. The cargo was switched using wires stretched between the ships and as underslung loads beneath helicopters. ‘Replenishment at Sea’ (R.A.S). is a mainstay of naval operations and is practised across the fleet, transferring everything from aircraft fuel to cornflakes. In this instance the parallel distance between the ships suddenly began decreasing rapidly, sandwiching a dangling Sea Dart missile between the hulls. As the tannoy screamed “stand by for collision Brace! Brace! Brace!” we were lucky enough to have a flight deck full of Sea Eagle Missiles and 1000lb bombs to hang on to. In some Trafalgar’esk moment, we half expected cutlass wielding boarding parties, to swing from the rigging. The entangled ships eventually unhitched themselves. applying some welcome distance with a few scratched but no serious damage. We completed the transfer and headed for home. The last night of a detachment is usually a pretty drunken affair. The sailors called it ‘up channel night’, typically because the ship would be cruising the home strait, up the English channel to Portsmouth. The crew would draw their beer ration of three tins, supplemented by the illegal squirrelling away of rations from previous days. Then on completion of duties and evening rounds, all would sit around the communal space in their mess for a social drink. After the tension of a deployment, the decompression is a release that follows a natural course. The forces and their families have long recognised its merits, but it is not with out risk. A sailors fertile imagination fuelled by alcohol and sense of humour, within the austere environment of a battleship can often descend into regrettable obliteration… We flew from the ship the following morning, hungover, stinking like pub carpets and throwing up in to a spare rotor blade’s tip sock. Our Flight Commander was not best please with us. In particular with two of the flight, who supported freshly shaved heads which would raise the wrong eyebrows back at base. Their drinking game losses already costing them withdrawal of shore leave, until their locks grew back to a number one length.

The two aircraft rattled their way down the country, from the top of Scotland towards Cornwall. A brain dead, blood shot mechanic tracking the route through his sonar well. As we flew over South Wales, I sat up and nudged Taff on my right, shouting into his ear defender ‘Hey Welsh we’re home!’ As the words left my mouth I felt our aircraft descend, then bank around in a tight circle. Looking around the cabin, concern flushed the faces of those all those with views. I craned to look out of the oily sponson window and caught sight of our sister aircraft -call sign 34 - spinning around on itself. We followed her auto gyrations to the Welsh floor, landing in a playground next to a primary school. I jumped out of the cabin door before the engines shut down, to check out the other aircraft. It had landed heavily on its undercarriage, instantly flipping over on to its side, its engines billowing smoke and rotor blades completely mangled or missing. Incredibly, its crew and passengers had already managed to scramble out and were looking back at their crippled ride, bewildered and relieved. As locals began to filter into the playing fields, stories and questions began to emerge, a blade had jammed into a road drain some streets away. A trail of shrapnel had peppered rooms in an old peoples home, bolts and washers had embedded in the walls around the park. Who were the bald guys? had we been transferring prisoners of war? Remarkably there were no casualties. My mum received her phone call from the staff officer as she watched footage of the scene on Wales Today.

Only a few of 34’s crew wanted to continue the journey by air. Those that didn’t, hung around to secure the crash site until the ground party arrived. With a revised and bolstered crew list, I strapped my self back in to the sonar well seat of 36 and we launched for Cornwall. As we crossed over the Bristol channel into England, red warning lights started flashing on the overhead panel between the pilots. The young pilot now sitting next to me had taken Taff’s place. He immediately jettisoned the oily sponson window between us with his elbow. I assumed he knew what was happening since he was connected to intercom. I felt some comfort sitting next to him, not only had he just survived the playground crash but he was also one of the two survivors from the crash off Eddystone Rock. I gave up trying to decipher what the aircrew were saying. The decibels noticeably reduced as they shut down one of the engines and the aircraft began to descend. Constrained to my useless seat, I carried out the only escape preparation open to me; I parted the sonar well curtain with my boots, to watch how quickly the ground might arrive. Thankfully it came gracefully in the form of RAF Chivenor, accompanied by foam spitting fire engines and blue flashing lights. This reception conjured up a sense of Déjà vu for me. My maiden voyage in a Seaking two years before, had also been interrupted by a similar emergency landing. In that case it was Plymouth airport on route to Portland’s Thursday War. At Chivenor the engineers onboard soon discovered blockages in the fuel systems, possibly sediments stirred up in the fuel from the earlier dramas. With the aircraft secure on a military base and not some random welsh playground, we left it there for the ‘Down Bird party’ to come and sort out, borrowed a van and completed the rest of our journey by road.

In the vicinity of a disaster, near miss, lucky escape or any of other incident, where fortune has smiled, I have definitely experienced a palpable sense of disconnection. Within a vast spectrum of close calls, there is plenty of anecdotal and scientific evidence recording the survivor's dissociative state. This might be a sensation of separation from the body or altered perception of time. Our species expertly deploys a ‘denial of death’ strategy that ruptures on these occasions. We habitually embrace a delusional sense of immortality, in order to avoid confronting the inevitability of our own death. This defence mechanism is both biological and cultural. It allows us to go about our day to day business, free from an overwhelming death anxiety. When we are confronted by a situation where death could quite easily have been an outcome, mortality salience interrupts our deluded status quo. This is a pre-human, fight or flight reflex to threatening environments. And it conjures up evolutionary adaptive responses, to solve, limit and combat a specific life threat. The military recognises and intentionally hijacks these evolutionary acute stress reflexes. They nurture, manipulate and enhance them through the a realm of fantasy. The Forces deploy the imagination and the pretend to train troops, create processes and test equipment. War Games, manoeuvres, exercises and drills are a continual occupation, created to familiarise soldiers with the chaos of war. They build up almost automative responses, patterns and frame works to navigate the unfamiliar. The anxieties of the nation motivate the Armed Forces to superpose imaginary scenarios on to a physical world to test their agency. It is a near impossible task! Time and again life proves just how incredible and unpredictable it is and how complacent and ill prepared the best of us are. In my life time 9/11 still seems as unimaginable today as it did then, even with a lifetime of Hollywood conditioning. How does someone like the little boy from Sherwood Crescent reconcile life? He knelt in a garage repairing his sister's bicycle. When, over the road, the disintegrating aircraft ‘Clipper Maid of the Seas’ suddenly reduces his house, sister and both parents to a crater before his young eyes. The vascular network of consequential emotions extend far beyond the friends and relatives who perished at Lockerbie. Amongst the stories were honeymooners, A musician, Olympic athletes, members of the United Nations and CIA on board that fatal Boeing. There were many near misses among them, Sex Pistol John Lydon who missed the flight due to an argument over luggage with his wife. The ‘Mannequin' and ‘Sex in the City' actress Kim Cattrall, postponed flying to buy a Harrods teapot for her mum. And Motown’s Four Tops, whose Top of the Pops recording of ‘Loco in Acapulco’ over ran and inadvertently saved their life. A passing lorry driver hearing the news on his CB radio joined one of the first search parties and recalled “seven or eight bodies lying around outside. They just looked like shop dummies. They didn’t have a mark on them. It seemed surreal. I later read that the pilot and engineer were still strapped in their seats.”

The pilot jettisoning the window next to me was an archetypal product of his drills. His normal working day involved practising helicopter escape, in theory, dry drills in the hanger, on the flight deck and wet drills in a swimming pool or simulator. His drills were further honed by real life, with two recent crashes in that many months and possibly another in the same day, he was on top of his game. In the Southern Approaches, strapped to his seat and disappearing underwater into the cold blackness. He was reliving an experience practised many times before in the underwater escape unit. But real life seldom matches the imagined, as he automatically tried to jettison the window near Eddystone, it wasn’t there. Not feeling any aircraft around him, he release the seat belt and floated to the surface. The other survivor from the this crash was the Observer. His equally comfy seat was -like the pilot’s -fitted with a life raft and sheep skin cover. It was positioned between two heavy pieces of sonar equipment that would sandwich the occupant in the event of a crash, earning itself the moniker ‘the dead mans seat’. Fortunately at Eddystone, he was relieved from this finality and like the second pilot spat from the wreckage still seated. It took several months in hospital to mend the Observers legs but he was eventually able to return to flying. The squadron thought it would be a nice touch to collect him from hospital in a helicopter. He didn’t quite share those sentiments when mechanical problems forced the Sea King to make an emergency stop in a field just outside Truro. I was sent to collect him in the Squadron van.

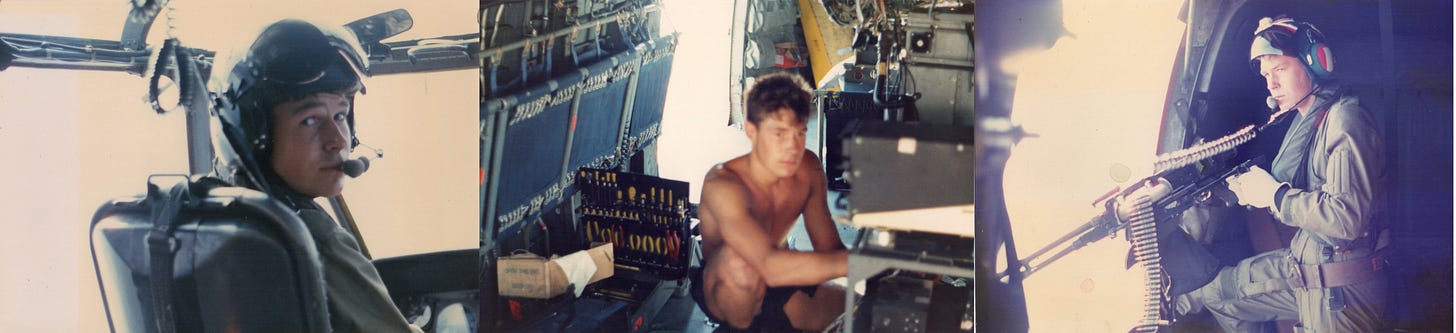

I don’t mind flying and realistic about the risks. But even today when I strap in for the long hauls and short, I can’t help visualising how the aircraft will break up on impact and muse over the safest seats. My time in the sonar well seat was eventful and short lived, not because I received promotion or seniority. It simply vanished when the role changed from anti-submarine in the Arctic to mine-hunting in the Gulf. The sonar was ripped out, its hole plugged and the equipment replaced with cameras, monitors, chaff, flare, secure speech and General Purpose Machine Gun (G.P.M.G). The tour offered me new opportunities to to explore more varied flying positions. I flew the aircraft from the second pilot’s position. A chance that certainly would not have presented itself, if the flight commander had known my track record driving a Ford Capri. Needless to say I was not a natural aviator, very relieved to hand back control to the first pilot. I was far more at home living the ‘Apocalypse Now’ dream behind the machine gun. Mounted in the cabin, we shot belts and belts of ammunition through the open cargo door. We targeted an improvised mine made out of a cardboard thrown from the aircraft. The expression to give ‘the whole nine yards” is said to have come from firing off, a full 9 yards of a Vickers machine gun ammunition belt. In reality a Vickers belt of 250-rounds is only only 6⅔ yards, my GPMG even shorter, but the 350 round in a US .50 Browning belt would legitimise the idiom. Although there are a few more complications with the origin myth, in the form of competitors; a three masted sailing ship has nine yard arms to rig its sails, making its top speed the full nine yards. And with fabric typically woven to this length, using the maximum amount of material to make a kilt would give a large Scottish man a very premium product. What ever the etymology, as we flew passed for the fourth time, I gave that floating box some Heart of Darkness “Get Some! Get Some!”. I delivered the last of our 2000 rounds and it floated away under the scorching Arab sun completely unscathed.

Colonel Muammar Gaddafi designed the green Libyan flag used during his 1977-2011 administration. At the time it was the only national flag in the world represented by a single block of colour. Several confrontations with the US Navy in the 1980s eventually lead to the Lockerbie bombing. In the aftermath Abdel Baset al-Megrahi stood a contested trial for the terrorism, standing before a panel of three Scottish judges he was sentenced to life. A protracted appeals process ensued over a likely miscarriage of justice, leading to his release on compassionate grounds due to terminal prostrate cancer. Gaddafi did accept responsibility in 2003 and paid compensation to the families of the victims, but the episode left a lasting post-traumatic legacy. It remains the United Kingdom’s deadliest terrorist attack and deadliest aviation disaster.

Draped over a flag pole and constructed from Ministry of Defence grade green flag weave material. The sculpture 'Clipper Maid of the Sea’ is a kilt made from a piece of fabric cut to the dimensions 747cms corresponding to the Boeing aircraft type 747 and 103 cms the flight number of the fatal PanAm flight 103